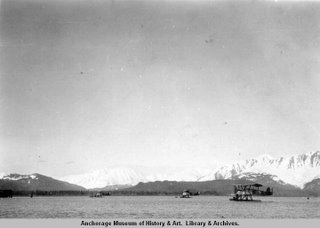

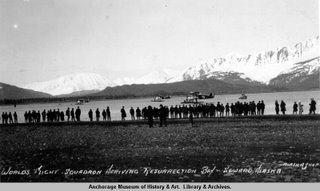

The unique sound of four 12-cylinder water-cooled 420-hp Liberty engines echoed as four Army flyers arrived in Seward on April 13th, 1924. The Douglas World Cruisers were the first airplanes ever seen by most of the 1,000 people who welcomed from the beaches of Resurrection Bay.

It was a time of frail airplanes built of wood, wire, and cloth, with uncertain engines, wooden propellers, and few instruments. The adventure began in early 1924, when US Army Air Force General William Mitchell predicted the strategic importance of Alaska in a future air war.

The announcement by the Army Air Force that eight of its airmen would attempt a round-the-world flight captured the world’s attention. British, Portuguese, French, Italian, and Argentine pilots immediately announced their intentions to claim the coveted title of first to circumnavigate the globe.

Donald W. Douglas, a young aircraft manufacturer of seaplanes in Santa Monica, agreed to build planes for the Americans based on his Navy DT-2 torpedo bomber but with significant changes for long-range operation. The airplanes, called Douglas World Cruisers, were dual-controlled with a gas capacity of 644 gallons for a range of 2,200 miles. They would each have engine instruments, altimeter, turn-and-bank indicator, drift indicator, and compass - but no radio.

On April 4, the Seattle, Chicago, Boston, and New Orleans, left Washington for Alaska. The 600 mile flight from Sitka to Seward took nearly seven hours and a half hours through the worst weather they had encountered to date.

“For a couple of hours the weather was ideal and then we started to run into snow squalls, light ones at first, and then heavier and heavier,” reported Lt. Leslie P. Arnold, the mechanic for the Chicago. “About 1:30 we struck a regular blizzard that lasted nearly 45 minutes, the thickest weather any of us had ever flown in. The only possible way to keep going was to fly along the beach just over the water and follow the black beach line. Several narrow escapes from collisions took place, and everyone breathed a sigh of relief when we finally broke through into brilliant sunshine.”

“From here on the weather was ideal, clear and sunny, and again the snow capped mountains were admired by all.” Arnold continued. “Quite a few glaciers were passed and being the first seen by many of us, they were given a keen looking over. They are nothing more or less than a river of solid snow and ice, yet to me it created quire a feeling of awe.”

There was no float plane dock at the boat harbor, so the Flyers were serviced by having two medium-sized dories shuttle drums of gasoline to the planes. The gasoline was pumped by hand-operated centrifugal pumps from the drum to the tanks. The oil, in five gallon cans, was poured by hand into the oil tanks.

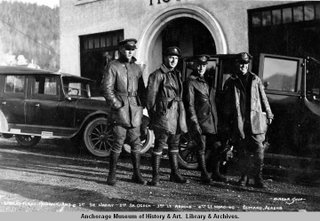

The soon-to-be world famous flyers were offered some of the most luxurious accommodations of their trip, spending the night at the Van Gilder. In her golden age, the Van Gilder was considered the finest hotel in Seward, catering to the wealthy passers-through, visiting dignitaries, travelers, and explorers.

The flight was challenging every step of the trip, and the Alaska leg was no exception. With flight commander Maj. Martin piloting, the Seattle fell behind with mechanical trouble that eventually forced him down. After an engine replacement, the Seattle departed in questionable weather hoping to catch up with the other flyers waiting at Dutch Harbor.

On April 30, the Seattle lost her battle with fog and high winds on the segment between Chignik and Dutch Harbor. They became lost and crashed on a mountainside near Port Moller. The airplane was completely destroyed. After walking ten days through the frozen wilderness, the two-man crew safely reached Dutch Harbor escaping with only minor injuries.

On September 28, the Douglas World Cruisers returned to Seattle with an actual flying time of 371 hours and 11 minutes. One of the flyers received his only injury from the trip, two broken ribs, when an overeager greeter at the Santa Monica Douglas plant reception gave him a bear hug.

Sources differ on whether they logged 29,000, 27,553, or 26,553 miles in six months and six days - averaging 70 mph. Whatever the actual distance, the 1924 round-the-world flight remains one of the truly great achievements in aviation.

More than just an aviation milestone, this flight was a monumental logistical accomplishment that was an important step towards opening up worldwide air transportation. The flight was the greatest feat in aviation up to that time, and earned the Douglas Aircraft Company its motto, “First Around the World.”

1 comment:

Enjoyed your Look Back at the Douglas Flyers. It was of the great events in the history of flight and you did a great job of telling that story.

Post a Comment