So long, Cecilia

By Debbie McKinney

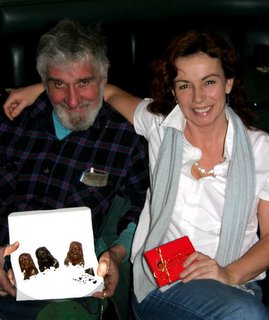

Anchorage Daily News reporter

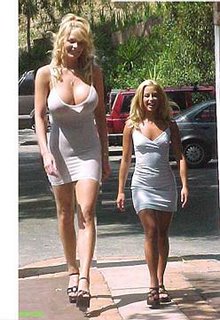

She prayed on flat-chested women: "Wanna hear a joke that will make your boobs fall off? Oh, I see you've already heard it."

And she was quick to divulge the facts: "Get the vital statistics down straight. My measurements from the bottom up are 37-29-49 1/2. Without a bra on, 37-29-52. On my hands and knees, I'm 37-29-60."

Cecilia "Ceil" Braund used to say if her age ever caught up to her bust size she'd throw "one hell of a party."

She didn't make it. She died of kidney failure. She was 43.

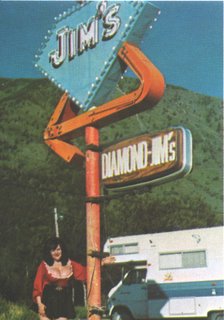

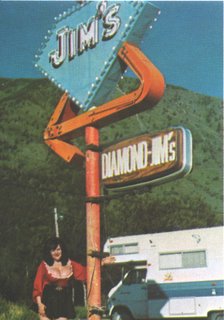

Ceil was an institution in the watering holes around Indian, most recently bartended of the now-defunct Bore Tide bar. The The few who knew the woman behind the antics saw a sensitive, warm-hearted person who valued her time alone, devoured books and expressed herself best through poetry.

The countless many who didn't saw only the flamboyant wigs, fur-lined miniskirts and mammoth-sized mammaries. But, then, you'd have to be blind not to see them. They weighed more than 14 pounds apiece and were insured by Lloyd's of London.

Ceil's clothes were custom made to flaunt what she considered to be her best attribute. Consequently, she always looked on the verge of falling out of her dress. But that only happened when she wanted it to.

Particularly during the pipeline years, men would line up to be photographed grinning with their heads buried amid Ceil's appendages, one on each side. "Alaska earmuffs." she called them.

Ceil especially liked the little old men from Florida who wanted Alaska earmuff pictures to hand in their retirement homes. She'd give them their earmuffs and they'd hobble off as happy as could be. That's what Ceil decided these anamalies were for - to make others happy.

She also liked to embarrass people. "Is that a package of Rolaids in your pocket?" she'd ask men. And she was always dropping things down her blouse. "If you can breathe through your ears, boy, you can go for it."

"That was Cecilia. God, what a character," says her brother, Randy Stimson of Portland, Ore. "She was a wild one. That's the only way you can put it."

Ceil was born in the farming community of Nine Miles Falls, Washington, at midnight on May 21. That put her walking the fine astrological line between Taurus and Gemini.

"Which is why I'm so screwed up, I think," Ceil said in the memoirs she taped before she died. "Leastways, it gives me an excuse. I should have known right of my life was going to be a little messed up. Being young and innocent, I went head with it anyway."

Ceil's father was an electonics genius who did secret work for the Navy during World War II. He had one of those mad-scientist personalities, her brother says. Preoccupied. Rather absent-minded.

"I'll tell you a little story about him," Stimson says. "He was so forgetful that when he got married, he went home iwthout mother from the reception. He forgot her."

One day when Ceil was an infant, her parents accidentlly left her on the couch and took a bundle of diapers to the church instead. No, this wasn't your typical famiy. "Screwiest outfit you ever met in your life," Stimson says.

He describes Ceil's childhood as "horribly complicated. Cecilia was too sensitive. When you were watching a football game and the teams huddled, they were talking about her."

Ceil was embarrassed by her breasts. At one point, she bound them to try to make the growing stop. She also force-fed herself, thinking she could grow into them. She once pushed her 5-foot-1 frame up to 195 pounds. But her breasts just got bigger and heavier.

"Her shoulders would bleed from carrying a brassiere around," Stimson says. "I'm talking about when she was in the sixth grade."

Ceil once told a reporter she tried to commit suicide. But instead of dying, she learned to think of her breasts like Joe E. Brown's mouth or Jimmy Durante's nose.

"The alternative was to be a real (jerk)," Stimson says. "Ceil and I are an awful lot alike. We found that laughing and telling jokes is the best way in the world to keep people away. And drinking...It's the best way to hide.

"I think Cecilia found her niche up here," Stimson says. "There's just no doubt in my mind. She loved the people up here. And they accepted her. Whatever the hell she wanted to be, she could be up here.

"God almightly, the people she knew. I went to the coroner's office to get her death certificate, they know Cecilia. The mortuary knows Cecilia. Just say 'Cecilia' and off you go."

Ceil was married five times. Her first marriage to a sailor lasted about 20 hours. "I was 14 and he was 28," she once said. "After we got married, we went to a motel room and he called his mother long distance and asked her what to do. So I packed my bags and had it annulled."

In 1971, Ceil and another husband honeymooned by bicycling from Anchorage to Reno, Nevada. They divorced immediately upon arrival, but it was an adventure nonetheless.

Ceil had started writing a book before she died. A description of the bicycle trip was the last thing she wrote:

"We had four water jugs, one with VO and one with vodka and two with water. Le me tell you, you cannot drink and ride. It zaps all your strength. Plus, it seems your bike doesn't want to go straight. Neither did my (breasts). And wherever (they) go, I go - and my bike and half the traffic."

But during her last couple years, Ceil became less anxious to display her breasts. "She got really tired of always having to be the life of the party," says her friend, Josue Altig. "It's a lot of work to make people laugh all the time.

"She was hounded..." adds Steve Sltig, who tended bar with Ceil. "Show us your (breasts). Give this guy earmffs. Let us take your picture.' And she got tired of people saying, 'I've known Ceil for 20 years and they didn't even know her (last) name."

Ceil also stared worrying about getting old. Her doctors suggested she undergo a breast reduction for health reasons. But Ceil refused; it had taken her that long to get used to them, she said.

"That was also the year she had to get glasses, her doctor told her she was going through menopause, and medicare sent her an application for a plot," Josue Altig says.

"But I think one of the hardest things for her was, she'd finally found a place where she had a family. And then the Bore Tide was sold and she had to leave."

After the Bore Tide was sold, Ceil worked briefly in Seward and Homer, then became ill and moved to Anchorage. Not only were her kidneys failing her, but her liver was shot.

"She drank a fifth of VO a day," Stimson says.

"I said, 'You know you're killing yourself? You're going to pay the fiddlers.' And she said, 'I know that. And when the time comes I'll just die." And she did just exactly what she said she was going to do. She drank herself to death.

"Ceil wanted to donate her parts to science. Doc and I talked about that. He said, 'There's nothing here worth donating.' I mean, she used them up.